What Lessons Will CMS Apply to CPC+ Initiative?

In announcing its Comprehensive Primary Care Plus model, CMS showed it has somewhat learned from its first go round.

CMS has long maintained that primary care is central to the transformation it is seeking to bring to the nation’s health system. Showing the strength of that conviction, in April the agency announced its largest-ever investment in advanced primary care to date: the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) model. The ambitious program builds on CMS’ original CPC initiative, which began in 2012 and is scheduled to end later this year.

CPC+, run by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), a branch of CMS that tests innovative payment systems, will be a five-year multi-payer program implemented in up to 20 regions. It could accommodate up to 5,000 practices, which would encompass more than 20,000 doctors and clinicians and the 25 million people they serve.

Primary-care practices will participate in one of two tracks. Practices in Track 2 will provide more comprehensive services for patients with complex medical and behavioral health needs. In Track 1, CMS will pay practices a monthly care management fee in addition to fee-for-service payments. In Track 2, practices will also receive a monthly care management fee and, instead of full Medicare fee-for-service payments they will receive a hybrid of reduced Medicare fee-for-service payments and up-front comprehensive primary-care payments.

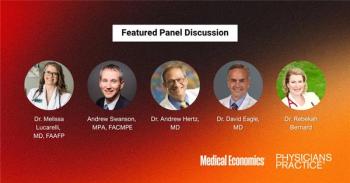

Physicians Practice asked several executives who focus on primary-care innovation to explain the positives and negatives from CMS with this initiative’s design.

Marci Nielsen, who has a doctorate and is president and CEO of the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC), said it is refreshing to see the federal government use a program like CPC as a proof of concept, and improve the model and scale it up in a way that adds fundamental improvements. PCPCC is a Washington, D.C.-based coalition that works to advance a strong foundation of primary care.

How does she believe CMS built upon the initial program? “First, they learned that shared savings component of this model was too complex,” Nielsen said. It was after the fact, and it was a source of frustration to providers. It needed some fine-tuning, she said. “Rather than shared savings, they give the money to the practices up front and then pull dollars if the practice isn’t successful in meeting performance targets. They tried to incorporate the component of behavioral economics that says people are much more apt to act if there is a fear of something being taken from them than they are apt to act if you dangle a carrot in front of them.”

In Track 2, CPC+ also moves toward global payments for physician practices that have experience with care management and health IT. “That is something we have been asking for from CMS for a long a time,” Nielsen said. “Those practices earn more dollars, but in return they agree to manage patients with complex needs, and speak to psycho-social needs and the various support needs those complex patients have. So for the first time, they are partnering with health IT vendors and saying you get to be a part of this, but when you participate, you have to be willing to help us figure out how to provide these complex patients with everything they need in terms of data flow. That has been a real barrier when you are taking care of really sick patients.”

Dylan Landers Nelson, a senior analyst focused on payment delivery reform for the National Business Group on Health (NBGH), also applauded the two-track approach. NBGH is a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization devoted to representing large employers' perspective on national health policy issues.

“We are expecting people who have been in practice for a long time and were trained under a different model to change the way they practice and take on these transformation activities, so while we are supportive of value-based purchasing and providers taking on risk, the multiple tracks is a good recognition of the fact that not everyone is ready to take on that amount of risk,” he said, adding that even the first track is pushing the CPC+ practices to be more aggressive in the way they do care coordination and outreach to patients.

Dinesh Sheth, CEO of Green Circle Health, which offers a platform for remote monitoring and patient-reported results, said the enthusiasm about CPC+ is justified. “It seems like CMS is taking a lesson about what work in CPC. It improved access to patients and risk stratification of patients. In creating the two tracks, it realized why some practices succeeded and some didn’t,” he said. It moves the people who are using portals, phone services, and advanced technologies to manage care complexities into Track 2 and Track 1 is more for beginners who have a certified EHR, but haven’t done much practice transformation work yet.

At least one participant in CPC is eager to work on the expansion. Speaking at the recent Health Datapalooza conference in Washington, D.C., Richard Shonk, a physician and the chief medical officer of the Health Collaborative in Cincinnati, spoke enthusiastically about both CPC and the potential for CPC+. The nonprofit Health Collaborative seeks to foster a connected system of through innovation, integration, and informatics in the greater Cincinnati region.

Cincinnati is one of the seven regions in the original CPC pilot, and Dr. Shonk leads the convening of payers and providers in the multi-stakeholder forum that conducts the initiative. He also oversees the practice improvement component of the initiative, guiding 75 local practices through the program milestones.

The CPC effort has been funded in a cooperative manner between payer and provider organizations, Shonk said. If the region is chosen for the CPC+ initiative, it would allow the organization to expand from 75 practices to 400 practices across the state. “That would allow us to spread the cost of data aggregation and decrease the costs for physicians and health plans,” he said.

How does the new program look from the patient and family perspective? Beverley Johnson, who serves as the President and CEO of the Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care, says CMS has been quite clear about partnering at every level with patients and families in clinical transformation. The Bethesda, Md.-based nonprofit IPFCC advances the understanding and practice of patient- and family-centered care through education, consultation, and technical assistance; materials development and information dissemination; research; and strategic partnerships.

The original CPC program spelled out five key functions, and each one involved partnering with patients and families, including having a patient and family advisory council. The CPC+ initiative also has those functions at its core. “I hope this is going to be interpreted as truly authentic partnerships with patients and their families involved in the design, implementation and evaluation of these changes,” she said.

Elsewhere, Johnson said the idea of better coordination with behavioral health providers and social services organizations is very promising. “Some of the most innovative projects we have observed or been a part of over the years involve partnerships with ‘nontraditional’ healthcare services,” she said. One of the sources of burnout in this country is that physicians feel like all this is on their shoulders alone, she added, and it really isn’t. “We are not asking them to do more. Patients and families want them to work differently, not do more.”

Tough Decisions on CPC+ and ACOs

As physicians try to navigate all the changes going on with accountable care organizations as well as impending implementation of the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, CPC+ represents another new program to factor into their reporting requirement equation.

CMS recently clarified that CPC+ is part of the Alternative Payment Model (APM) program, but this does not automatically exempt providers from MIPS reporting. For that, they must meet certain patient and payment thresholds. Furthermore, the fact that CMS announced that providers are prohibited from participating in both CPC+ and Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) ACOs introduces some complications.

Martie Ross, a principal in the Kansas City office of consulting firm Pershing Yoakley & Associates (PYA), used an ACO her firm is working with to illustrate one such conundrum. The ACO has every intention of staying in the program and has a strong primary-care base. Now the primary-care physicians have this offer to get money upfront if they participate in CPC+, she said.

The renewing ACO has to submit letter of intent by May 27 and have a completed application by July 29. “You won’t even know if you are in a region eligible for CPC+ until July 15. The ACO needs to know if their primary-care physicians are going to jump ship,” she said. The application for providers for CPC+ is Sept. 15. That corresponds within a few days of the typical deadline for MSSP ACOs to provide their full participant list, she explained. An ACO has to hit 5,000 attributed Medicare beneficiaries, and that is almost completely dependent on their primary-care physicians.

“The question CMS needs to answer,” Ross said, “is can you go ahead and be listed as an MSSP ACO participant and also submit an application for CPC+, given the potential that your application may be rejected for CPC+?”

Shari Davidson, vice president of the National Business Group on Health, said her organization was also disappointed that pediatricians were not included in CPC+. There are two M’s in CMMI, she noted, and Medicaid needs pediatrician medical homes and employers need pediatrician homes. “We hope they will figure out a way to deal with that issue. The good news is they are willing to innovate,” she said,

Multi-payer importance

Nielsen said the multi-payer aspect of CPC+ is crucial to its success. In the initial CPC program, CMS found 38 payers in the commercial space who were willing to partner with both Medicare and Medicaid.

“That’s important because the administrative burden for physician practices is so onerous because payers want different things from them. They pay differently and they want different reports on performance,” she said. “If you say to the payers, let’s all pay the same way and let’s give data back to the practices in the same way and let’s measure success in the same way, then the practices get to focus on patients.”

NBGH’s Landers Nelson agrees: “From our perspective, payers getting aligned to make sure there are common expectations of providers and their teams, as well as common measurements and financial expectations, can only mean good things. It allows the primary-care practices to be more efficient, and have clear expectations of what they should be working on.”

Another potential issue is that observers have noted that analyses of the initial CPC program have not yet shown meaningful changes in claims expense, clinical outcomes, or the patient experience of care. After the second year of the program, the analysis from independent research organization Mathematica noted that the practices “have not yet shown savings in expenditures for Medicare Parts A and B after accounting for care-management fees, nor have they shown an appreciable improvement in the quality of care or patient experience.”

But others argue that more time is needed and the program is on the right track. “When you are trying to bring about clinical transformation as well as cultural transformation, it does not happen in one or two years,” said the Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care’s Johnson. “Unfortunately both foundations and the government have created expectations that we are going to get instant results, not only in changing the practices but also in the way the public interfaces with healthcare.”

Nielsen added that it does take a while for practices to figure out how to use numbers and metrics to actually drive change. “It is one thing to see gaps in care relative to diabetes,” she said. “It is another thing to translate the data around your gaps in care into what you are going to do about it.”

Davidson said NBGH is excited to track employers that participate in CPC+ and share their stories with others. “If they improve health and save money, then others jump in, so we are going to stay close to this and watch the data and talk to employers. This has got to be a public/private partnership to be successful.”

Newsletter

Optimize your practice with the Physicians Practice newsletter, offering management pearls, leadership tips, and business strategies tailored for practice administrators and physicians of any specialty.