- Industry News

- Access and Reimbursement

- Law & Malpractice

- Coding & Documentation

- Practice Management

- Finance

- Technology

- Patient Engagement & Communications

- Billing & Collections

- Staffing & Salary

When the doctor becomes the patient

Oncologist Kamal Malaker unexpectedly found himself in need of heart surgery. The experience changed the way he practices medicine.

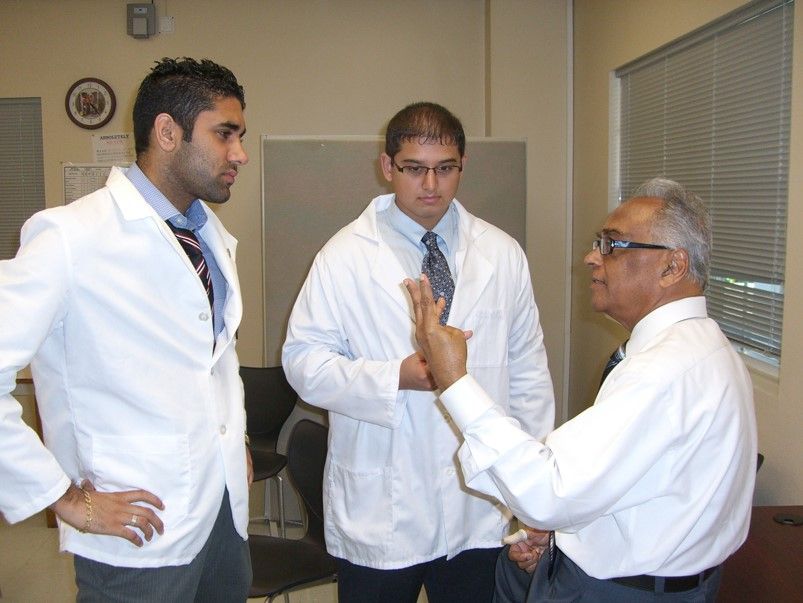

Photo courtesy Kamal Malaker, MD, PhD

In 2008, Kamal Malaker, MD, PhD, was driving through the night to catch a plane to go home. Once he was home, Malaker had trouble sleeping for four nights. He went to his primary care physician because he thought he had gastritis. Instead, Malaker’s doctor drove him to a cardiologist.

As someone who never had a heart problem, or any major health problems, it came as a surprise to Malaker that he needed bypass surgery.

In 2018, Malaker released a book called It is 7 a.m. in the Cardiac Ward, which traces his 11-day journey from doctor to patient. From intake to recovery, his book details the ups and downs of surgery, making friends with fellow patients and staff, and highlights the importance of empathy for medical professionals.

Malaker currently serves as director of clinical oncology at the Cancer Centre for Eastern Caribbean in Antigua, where he also teaches. He previously headed the radiation oncology department at Care Center Manitoba and at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. He has worked in England, Libya, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Sierra Leone. He was also a researcher at the Dana-Farber Cancer Center in Boston. Malaker has published multiple books and more than 100 scientific papers. In April, he presented at the International Keloid Symposium in Beijing.

Malaker spoke to us from his home in Winnipeg, Manitoba in Canada about how being a patient taught him how to be a better physician.

Why did you want to write this book?

Kamal Malaker: I work in the medical profession, and I teach graduate medical students. One of my students asked me how he can become a good doctor like me. I told him all you must do is exchange shoes with your patient. Then, I realized I had a long episode for my heart operation. I thought I could explain the entire process, surgery, and recovery as the doctor and as the patient. It’s a way of explaining the process to budding doctors and fellow colleagues about how we’re examining and treating our patients.

Despite undergoing heart surgery, you say that you believe the glass is always half full. Did you find you were the most optimistic person in the process of surgery?

KM: [Laughs]. I had no choice, you know? The surgery was done in Winnipeg. The Canadian health care system is excellent. I have no complaints. Canada has the high technological quality you’d find at Harvard or John Hopkins. All the staff of the cardiology ward of St. Boniface Hospital gave me their concern, kindness, and attention.

What was it like eating at a hospital as a gluten-free patient?

KM: I can’t have gluten. I am wheat intolerant, but wheat is a main staple as a food in a hospital. I had to discuss it with the doctors. People thought at that time gluten-free was a choice. It wasn’t.

Did heart surgery change how you practice oncology?

KM: Absolutely, no question. It certainly had an impact on myself, and it helped me connect to my colleagues. It also changed my relationship with my patients. I now spend a lot more time, even though there is limited time, to listen to patients when they come asking for help. Whatever they want to talk to me about, I listen. When I listen to patients, I try to hear what they’re not telling me, too.

At one point in the book, you reminisce upon advice your former medical professor gave you 50 years ago. He said, “Remember to do the best for your patients [or], for that matter, anyone who asks for your help. Help with your heart, mind, and hands and leave the result to happen.” What advice do you give to doctors today?

KM: Doctors have become such technical people in a technical profession. They forget to deal with patients as human beings. That’s the first thing we should come back to when dealing with patients. They’re not an object. They’re human beings. This is not taught in medical school.

At home, I don’t think parents have time to teach their children how to be human beings. That is what most is sadly missing in our practice nowadays. I would really place an emphasis on that to every medical student - and to everyone else.

Reducing burnout with medical scribes

November 29th 2021Physicians Practice® spoke with Fernando Mendoza, MD, FAAP, FACEP, the founder and CEO of Scrivas, LLC, about the rising rates of reported burnout among physicians and how medical scribes might be able to alleviate some pressures from physicians.

Cognitive Biases in Healthcare

September 27th 2021Physicians Practice® spoke with Dr. Nada Elbuluk, practicing dermatologist and director of clinical impact at VisualDx, about how cognitive biases present themselves in care strategies and how the industry can begin to work to overcome these biases.